Dyslexic and Loving Words asks the question – “What if you’re dyslexic but you love to write or use words?” Through interviews with seven successful dyslexic wordsmiths, the film highlights how it’s possible to overcome dyslexic issues, or work around the challenges they present, if you have a passion for words.

Here’s a piece I wrote for NAWE (National Association of Writers in Education) in 2014 following making Dyslexic & Loving Words, a film about dyslexic wordsmiths.

Dyslexic and Loving Words (published by NAWE 2014)

Someone I was working with recently recalled being asked some years ago, “Why are you studying words if you have difficulty with them?” My colleague had been granted help for his dyslexia while studying English Literature. The rhetorical question came from a support officer at Uni. I understood immediately why the comment had stayed with him.

Every dyslexic writer I have spoken to or interviewed recently, like me, has a database of similarly disheartening comments in their head about their relationship with words. Some are judgements from other people that still sting, others are our own internal self-doubts triggered by the likes of bad schooling experiences, personal frustrations or wider expectations around the correct use of English.

Every dyslexic writer I have spoken to or interviewed recently, like me, has a database of similarly disheartening comments in their head about their relationship with words. Some are judgements from other people that still sting, others are our own internal self-doubts triggered by the likes of bad schooling experiences, personal frustrations or wider expectations around the correct use of English.

Considering what is generally known about dyslexia, it’s no surprise to me that there is an assumption that someone who finds reading and writing challenging wouldn’t want to deal with words beyond necessity. Nor, in a society where grammar enthusiasts are often comfortable with being referred to as ‘Nazis’, and Michael Gove is able to cause ever-increasing regression in education, is it a surprise that dyslexics often don’t feel comfortable joining the word party. This bothers me a great deal.

As a child I loved words but as school made me anxious around them, and nobody encouraged me otherwise, I didn’t think I was capable of doing anything substantial with them. As a result, it wasn’t until after a Fine Art degree and some years into my creative career that I gained the confidence to take my passion for words and my secret scribbling more seriously.

Self-actualising

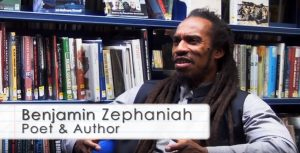

When I first started teaching journalism and creative writing in 2004 through Cube Magazine, a young people’s work experience programme and magazine, I remember how refreshing it was to hear performance poet, Benjamin Zephaniah, speak about his dyslexia with two 14-year-old journalists. This crucially marked the beginning of many magical moments when I have been privileged to witness the enlightening affects of inspirational talents speaking directly and passionately to young minds about everything from politics to comedy.

When I first started teaching journalism and creative writing in 2004 through Cube Magazine, a young people’s work experience programme and magazine, I remember how refreshing it was to hear performance poet, Benjamin Zephaniah, speak about his dyslexia with two 14-year-old journalists. This crucially marked the beginning of many magical moments when I have been privileged to witness the enlightening affects of inspirational talents speaking directly and passionately to young minds about everything from politics to comedy.

Seeing how these types of experiences can help young people to actualise their interests and aptitudes at a key stage in their development, I started thinking about how I could use my skills to both encourage and inspire dyslexic writers and tackle some of the misconceptions around the condition.

Taking things further

In 2012, following a stimulating debate about dyslexia at Sheffield’s Off the Shelf Festival of Words, I pitched the idea to the organisers about joining forces to make and showcase a documentary with these aims. My intention was to interview successful dyslexic writers about what has helped and hindered them in overcoming their difficulties and to explain, as simply as possible, what our challenges with words actually are. Thankfully the team were enthusiastic and ‘Dyslexic and Loving Words’ was born, realised and subsequently premiered at Off the Shelf 2013.

In 2012, following a stimulating debate about dyslexia at Sheffield’s Off the Shelf Festival of Words, I pitched the idea to the organisers about joining forces to make and showcase a documentary with these aims. My intention was to interview successful dyslexic writers about what has helped and hindered them in overcoming their difficulties and to explain, as simply as possible, what our challenges with words actually are. Thankfully the team were enthusiastic and ‘Dyslexic and Loving Words’ was born, realised and subsequently premiered at Off the Shelf 2013.

Being a pedantic perfectionist, (a nightmare affliction for a dyslexic writer, let me tell you), and some would argue because of my dyslexic ‘big picture’ thinking, I like to leave no stone unturned. But alas, there’s only so much you can fit into a film of this nature. One of the things I want to elaborate on here is just how off the mark the belief that dyslexia is an excuse for being ‘thick and lazy’ actually is. As neuroscientist, John Stein explains in the film, this was the dominant thinking when he began studying dyslexia some thirty odd years ago. I had no idea how prevalent this view still is until I started my research.

Here’s the thing…

I believe I speak for many dyslexic writers who want to be taken seriously when I say; we battle very hard to eliminate the mistakes we make in order to be treated equally to other non-dyslexics on the merits of our work. We don’t want special treatment when it comes to the quality of our writing, but our difficulties mean we often work much slower and, despite our best efforts and all the will in the world, we will miss things and make mistakes more often than non-dyslexics. So for all you proud Grammar Nazis, feelings of shame are counterproductive; we care too but this is our reality. In a recent creative writing master-class at Sheffield Hallam University, it was good to hear literary agent, Meg Davis, point out that in her experience, dyslexic writers are often the most conscientious about the proofreading of work.

I believe I speak for many dyslexic writers who want to be taken seriously when I say; we battle very hard to eliminate the mistakes we make in order to be treated equally to other non-dyslexics on the merits of our work. We don’t want special treatment when it comes to the quality of our writing, but our difficulties mean we often work much slower and, despite our best efforts and all the will in the world, we will miss things and make mistakes more often than non-dyslexics. So for all you proud Grammar Nazis, feelings of shame are counterproductive; we care too but this is our reality. In a recent creative writing master-class at Sheffield Hallam University, it was good to hear literary agent, Meg Davis, point out that in her experience, dyslexic writers are often the most conscientious about the proofreading of work.

But back to shame, because it is, more often than not, the thing that really stifles and holds dyslexics back. Many either don’t admit they are dyslexic, and in fact go to great lengths to hide it (thus missing out on support), or have never even been diagnosed so end up feeling self-conscious and stupid anyway. I got my diagnosis about ten years ago but a lot of damage to my confidence was already done and a lot of what I could have been achieving, I wouldn’t have dared consider.

Champion difference

Key to the film is the question of how we can nurture young dyslexic word-lovers and prevent them from having the same kind of negative educational and social experiences that all in the film have endured. If current changes in education are anything to go by, we’re doomed, but if we listen to Lily, the 11-year-old interviewee who rightly has the last word in the film, the future is bright. Lily is an example of fine parenting and positive intervention at an early age. Ultimately, we need to keep stimulating a serious shift in thinking beyond formal education; the need for nurture to aid nature in a wider context is more vital than ever.

Key to the film is the question of how we can nurture young dyslexic word-lovers and prevent them from having the same kind of negative educational and social experiences that all in the film have endured. If current changes in education are anything to go by, we’re doomed, but if we listen to Lily, the 11-year-old interviewee who rightly has the last word in the film, the future is bright. Lily is an example of fine parenting and positive intervention at an early age. Ultimately, we need to keep stimulating a serious shift in thinking beyond formal education; the need for nurture to aid nature in a wider context is more vital than ever.

I urge all teachers of creative writing, in fact all teachers, to watch this film and get a sense of what around 1 in 15 of us are dealing with. Better still, actively champion dyslexics, be curious, ask questions, let us know that you might not ‘get it’, but you certainly don’t judge. And if you’re really curious, imagine this: You get a great idea for a poem or a story and you can hear sentences forming beautifully, rhythmically inside your head. It’s all ready to flow out. But today, you’re only able to write with the hand you have never written with before. Have a go. Feel the distraction of trying to work out how your hand should move to form each letter and then the frustration as the words slip away. This gives a little sense of what it feels like, certainly in terms of writing, to be dyslexic.

Despite its challenges, many specialists and dyslexics themselves believe the condition is a gift; a way of seeing and thinking that offers particular strengths. There is currently no conclusive evidence of any certain advantages that define it, but, if only by experience, it has provided me with a different perspective and I hope, stronger sense and sensibility in my mentoring and teaching roles. I work in creative education with young people from all backgrounds, educational opportunities and levels of privilege and I agree with education specialist Ken Robinson, who is quoted in the film; if we celebrate and nurture our creativity, curiosity and diversity as humans we will flourish. No matter what Gove peddles, encouraging children to engage with and understand the meaning and power of words is far more important, and fruitful in the long run, than getting everything ‘right’.

Recent Comments